By Ashwak Fardoush

Ashwak Fardoush is a writer, writing coach and teaching artist, who recently facilitated the Writing Workshop for older adults at India Home’s Desi Senior Center.

[social_share/]

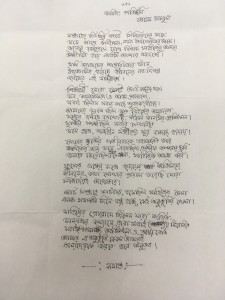

The room buzzed with anticipation. The smell of cooked chickpeas and onion lentil fritters served to the guests still lingered in the air. Children’s cries rang out in the background. Amidst the noise, Salema Khatun took the stage. She recited her poem, “Shadhinota” (translated as “Independence”), alluding to the Liberation War of 1971 in Bangladesh. I felt proud as I watched her read her poem to the audience.

On the evening of May 19, 2017, we were at the Culminating Event for a Writing Workshop organized by India Home for its members at the Desi Senior Center. The event was also a Pre-Ramadan Celebration and a happy and proud occasion for our members. This was the open mic portion of the event

“I had put away my writing for twenty years. …. But I have written four poems in your class.”

Salema Khatun crafted that poem over the course of a few weeks. She had attended a writing workshop that I facilitated at the Desi Senior Center. Inspired by a prompt at a workshop session, she wrote a poem that she finished at home, writing a few lines at a time in between her household chores, showing me the progress along the way, and adding the final two lines because she wanted the poem to be a sonnet. Just the day before the event, Salema Khatun told me, “I had put away my writing for twenty years. After my husband’s death, I took on the full responsibility of my family. But I have written four poems in your class. Look what you have done for me.”

Seniors tell their stories through poems and memoir

Salema Khatun was one of the eight participants who were part of a bilingual memoir writing workshop* at the Desi Senior Center. This workshop was designed to help seniors tell their stories. This pilot program was a collaborative effort, making the phrase “it takes a village” truer than ever. The staff from India Home and the Desi Senior Center—especially Lakshman Kalasapudi, Nargis Ahmed and Meera Venugopal—worked tirelessly to make sure the seniors had a great writing experience.

As I heard Salema Khatun’s voice rise and fall, I remembered the first day of the writing workshop. It was a Thursday morning. I was setting up the classroom in one corner of the prayer room. Some were still praying on the other side of the room. I arranged the chairs in a circle and laid out the attendance sheet and the writing supplies on a chair. I had thought about the content and the structure of the workshop for the past two weeks. I even had a bare-boned lesson plan for the first session. Yet, I knew that I couldn’t plan out all the sessions. I was not teaching these participants. Instead, I was holding the space for the participants to tell their stories—stories that danced inside their bodies, that rested inside their eyes, that settled on their skin. I simply needed to let these stories surface on the page. While facilitating the workshop was not like any other teaching experience I had in the past—the participants were a few decades older than me, and the sessions were conducted entirely in Bengali—the advice I gave myself remained the same: I must keep my heart open, stay present and be curious.

Writing prompts and stories that unfolded against the backdrop of history

There were eight participants who made up the core group: Md. Hoque, Md. Mokbul Hossain, Rafiqul Islam, Salema Khatun, Haque Mohammad, Quamrun Nahar, Md. Abu Sayeed, and Farida Talukdar. I did not know what to expect each session. By the second session, I stopped bringing a thorough plan. The participants were vivacious, creative, mischievous, intelligent, wise, and in awe of life. We would always begin with a writing prompt from my plan, but then the session would unfold in ways I could never predict. We would write spontaneously. Soon, I became adept at reading what the group wanted in that moment in order to serve them and their writing.

Each session the participants excavated memories from their long, rich, vibrant lives and shaped them into poems and personal essays. When I closed my eyes, I could see the writers leaning over their marble notebooks, and scribbling away. Sometimes we would travel to far-flung places or go deep within ourselves. Sometimes personal stories would unfold against the backdrop of history.

At times, the participants tried to write out a decade of their life during a session. Sometimes, I would ask the participants to scrawl a word on an index card, fold it and put it inside a mason jar. Then, I would ask a participant to pick a word out of the jar randomly and the group would write about that word. The first word picked out of the jar was “baba” (translated as “father”). Writers wrote about their love stories, their childhood friendships, and their son’s letters back home.

Participants eager to share their writing

Every session was memorable in some way. Once, I remembered seeing Md. Hoque writing in his notebook a few steps away from the class. Since the session was about to start, I gently asked him to come inside. He nodded, but his head was still buried in the notebook. A few minutes later, he entered the classroom and announced that he had just finished writing a poem. He not only addressed this poem to another participant, Md. Mokbul Hossain, but he also challenged his peer to respond back in the form of a poem. Md. Mukbul Hossain was deemed as the poet of the group. Even before the workshop, he had a moleskin notebook with poems written in his beautiful penmanship. He once showed me a poem he wrote in his notebook. The first line was a question a stranger posed him on his walk. He told me that he carried his notebook with him so that he could write down any detail, mundane or not, that can turn into a poem someday. Needless to say, Md. Mukbul Hossain managed to cobble together words to pen a poem to respond to Md. Hoque’s friendly challenge in class that day.

Abu Sayeed was another participant in the workshop. He took two trains and a bus to travel from Brooklyn to the senior center in Queens. Before the first day of class, he told me of his interest in the writing workshop. He shared that his life was full of “korun” (tragic) stories and wondered if it was okay for him to write about those stories in the workshop. “Yes,” I said. “Life is full of joy and sorrow. Sounds like you have lived and have stories to tell! Please come and write with us.” So, he did. Md. Abu Sayeed would read his stories out loud in a voice that would tremble and crack at times. We would all listen, understanding the gravity of the moment and our role in it.

I was surprised by how eager everyone was to share their writing with each other. The ink would still be fresh on the page, our head would still reel from the memories we had dredged up on the page. Yet, the participants were ready to share their writing immediately. Quamrun Nahar read about scaling a tree as a child and falling down from it one day when she was stung by bees. She was carried to the kitchen where her grandmother rubbed garam masala paste all over her body. In a similar vein, Farida Talukdar often shared her anecdotes. We rarely made past the first writing prompt. The pieces people shared after the first prompt would inspire others to share their personal stories or debate passionately about a topic that surfaced in someone’s writing. We found ourselves discussing how in-laws’ relationship should be toward their children’s spouses, the struggles with upholding the Bengali language and culture in the United States, and the political climate in Bangladesh.

Teacher as Witness

Nancy Agabian, an author and founder of Heightening Stories, told me that the participants were “lucky to have [me] as their teacher and a witness.” That word, “witness” was the summation of my role. These participants contain a lifetime of memories and the workshop became a space where these writers got to share their testimonies—tales suffused with pain, joy, love, loss, dreams and despair—and were witnessed with respect and camaraderie. Md. Hoque wrote so poignantly on the last day of the workshop: “will we remember the stories of the three sisters and five brothers, a family meeting for a literature class lasting but for a short while?”

Council Member Daneek Miller and his wife, were among the guests of honor at the celebration. CM Miller handed out certificates to seniors who participated in the workshop

At the event, I looked to the stage once more. Salema Khatun had finished reading her poem. She paused for a moment and looked out at the audience. The crowd broke out into applause. Salema Khatun walked off stage. I smiled and then closed my eyes: I imagined the participants pulling out their marble notebooks and writing away with their ball point pens, putting one word after the next word after the next to tell all the stories they held inside of them until they were spent, until they were empty, until they were fully satisfied.

*This Writing Workshop was funded in part by Poets & Writers with public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

You can read the full publication of the writings by clicking here.