[social_share/]

Three mornings a week, Abu Sayeed, 64, wakes up in his home in Cyprus Hills in Brooklyn, NY, worrying about the subway. He wonders if he’ll manage get the right train? How long will he have to wait? As he gets ready for his long walk to the station – putting on a cap, a thick sweater, sports shoes – he worries if he’ll make it in time to catch the exercise class he loves so much at the Desi Senior Center in faraway Jamaica, Queens.

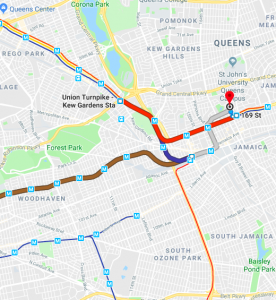

His journey begins at the Cypress Hills subway station in Brooklyn where he catches the J train to the Sutphin Boulevard station in Queens. From there he transfers to the E train for Kew Gardens. At Kew Gardens he waits for the F train to Jamaica’s 169th street station.

Three trains and 70 minutes after he first got into the subway, he emerges into the light at Hillside Avenue and walks up the slope to the Desi Senior Center. He’s timed the walk: it takes a further 8 minutes.

Abu Sayeed has to take 3 trains and travel for more than an hour to get to India Home’s Desi Senior Center. Lack of convenient transportation increases the social isolation and decreases the wellbeing of our immigrant seniors.

Refuge from Social Isolation

Abu Sayeed has made this complicated journey, three times a week, ever since the Desi Senior Center opened in 2014. “My three arteries was blocked so I had three bypass operations. But still I came,” he says, proud of his tenacity. “I am coming here since day one. December 15, 2014.” His eyes crinkle under his cap. We are in the office of India Home’s Desi Senior Center in Jamaica. Outside the door, other older adults at the center have finished their lunch of rice and chicken curry are munching on apples for desert. A few pop in now and then to say hello to Sayeed or to ask questions of the staff.

So why, given the time and effort it takes, does he make this journey day after day?

Abu Sayeed doesn’t hesitate. “The friendliness of all the people here is very important to me. It is something that I enjoy every much,” is how Sayeed explains his dedication.

For Sayeed, and others like him, the Desi Senior Center, catering to mostly Bengali muslims and other immigrants from South Asia, is a refuge from social isolation, a problem that more and more elderly face in New York city. Sayeed moved from Bangladesh in 2008 to join his children in the US. His sons are busy, off at work or college, leaving Sayeed and his wife alone at home. In the summer he putters around growing flowers and vegetables in his small garden, but in the winter, there’s nothing to do. “My wife is idle,” he mock-laments. She’s happy to stay home. But he gets bored.

At the Desi Senior Center he meets older adults from his country who share the same language and culture, people with whom he can laugh or talk politics with for a few hours a day. There are other reasons that draw him here: “There is a group exercise session that happens every day that I really like. That is the main reason why I come here. They also serve halal food which, especially for me, is very important.”

Food that is culturally suited, exercise, a friendly face: Sayeed’s needs are simple. Yet the journey to enjoy a few hours of small comforts is difficult.

The burden of transportation costs

Finding easily accessible public transportation is one problem; the high cost of transportation is another. Sayeed, who retired as a manager at a fertilizer plant in Bangladesh, has no work history in the US and thus has no social security income to draw upon. The cost can become a burden: “Every day I am spending $5.50…that is a lot if you don’t have a job.” he says. Selvia Sikder is a case management worker at India Home: “New York City requires that older adults have to be 65+ to get the reduced fare Metrocard. Many of our elders who don’t meet the criteria, even those who are below the poverty line, are spending $5 dollars a day to get to the center.” They can’t access private transportation services because these seniors are often on Medicaid, and these services are not available to those on the Medicaid plan.

There are days when Sayeed simply doesn’t have money and waits for some kind soul to swipe him through the turnstile.

Still, not all elders are as determined or as healthy as Sayeed. “Many elders have to beg for a ride to come to the center. Or wait for family to come and pick up. Some can’t afford even the reduced fare of $1.35. Others live far away from the nearest subway or bus-stop and find it difficult to walk,” Selvia, the case worker, explained.

Fast Growing Elderly Population Needs Better Options

New York City’s large older adult population includes 1.4 million people over the age of 60 and the fastest growing segment of this population are immigrant seniors. The 2013 poverty rate among those age 65 and over was 21.6%. Given these statistics, one would think that NYC would make improving the public transportation system for the elderly a priority. However, the global design and consulting firm Arcadis’s Sustainable Cities Mobility index 2017 published in 2017 found that NYC’s public transportation system was ranked 23rd in the world. Funding concerns, long commute times and looming mega projects kept the city out of the top tier.

New York City’s Department for the Aging (DFTA) funds 14 transportation only programs, which provide means of transportation to older and frail adults, according to a concept paper released in 2015. However these programs serve a limited number of community districts. Many community districts in Brooklyn and Queens remain without a ready source that can provide transportation to older adults.

The benefits of older adults being able to use a low-cost, easily accessed public transportation system are well documented. In January 2017, Reuters reported on a UK study that followed 18,000 older adults for more than a decade. Eliminating cost as a barrier to traveling around town was seen as an important way to improve the mental health of older adults by reducing loneliness and lack of social engagement.

By 2040 the older adult population of New York city is set to grow by 31%. Without proper transportation infrastructure that works for the aging, older adults like Abu Sayeed will face increasing social isolation and the physical and mental health issues that come with it. For now, though Abu Sayeed is looking forward to turning 65. “After 1 yr and 4 months I’ll get my half-fare Metro Card.” He grins in anticipation. “Almost there,” he says.

[stextbox id=’alert’ caption=’Recommendations’ collapsing=”false”]

Here are some of the recommendations that AARP (American Association of Retired Persons) urged on Congress in 2012. Many of them could be applied in NYC today.

- Dedicate increased funding for public transportation and the specialized transportation program for older adults and persons with disabilities.

- Include support for operations to help mitigate the high cost of gas and other expenses.

- Strengthen the coordination of public transportation and transportation provided by human services programs, such as agencies that provide transportation for seniors to group meals

- Ensure that older Americans have greater involvement in developing transportation plans to meet their needs.

- Ensure that state departments of transportation retain their authority to use a portion of their highway funds for transit projects and programs.

- Include a Complete Streets policy to ensure that streets and intersections around transit stops are safe and convenient.

[/stextbox]